“Movement lawyering means taking direction from directly impacted communities and from organizers, as opposed to imposing our leadership or expertise as legal advocates. It means building the power of the people, not the power of the law.”

I have been thinking about power and movements and how we practice the principles of movement lawyering inside and outside Columbia Legal Services.

There has been so much happening in the world. One thought, feeling, issue that seemed to be part of many conversations over the past few months is power – who has it, what is it, how does it play out at the organization I work at and in the world.

For myself as I am trying to learn and change as I continue to come to terms with the power and what I do with the power I have in the world. Sometimes I feel powerless. I have felt powerless to change the world, Columbia Legal Services, others, and sometimes even myself. And yet others see me as having a tremendous amount of power. And I do have power. And just saying that feels odd. And yet it’s true.

About six years ago, some community folks told me I was misusing my power. I did not understand what they meant. That was a difficult time for me. I felt ashamed, embarrassed, and confused. I thought I was trying as hard as I could. In my mind I was just a staff attorney who had tried to make some changes inside and outside the organization and failed to some extent. I did not have an anti-racist analysis or understanding of racial hierarchy. I had to work through my own intense feelings and take responsibility for my actions.

Part of the work for me was examining my relationship to power.

It took me awhile to understand all the places I had power in our current system whether I wanted that power or not – I had to deeply come to terms with what it meant to be white in this country and to see all the places large and small I had power – being white (assumed to be law abiding, knowledgeable, and safe), a lawyer, able bodied, speaking English as a first language, owning a home, moving into the middle class status, not having been convicted of a crime or have a criminal record even though I engaged in criminal behavior, citizenship, working at an organization with access to the power structures of the courts and legislative bodies, speaking and writing in ways that are valued in legal culture, healthy food, electricity, water, access to institutions like marriage if I wanted it, a safe home, freedom to move about my neighborhood, city, state, and country, having identification. There are more.

This power doesn’t mean that I don’t feel sad, unsafe, or oppressed sometimes. I do. Just recently I was refused entry into a restroom at a grocery store based on my gender queerness/fluidity. I know what it’s like to be hungry, to be held in restraints, to not have a home, to have been poor, to have been the victim of violence and abuse, to be on welfare, and yet my history and my queerness do not relieve me of my responsibility to understand my own power and what it means for me to be white in this country.

I have to recognize where I have power because when I do not I can harm others without any intent to do so. I can be kind, have read 10 books on history and racism and go to protests, but if I do not accept and be accountable for my own personal power, my own racism, my behavior, and my impact, then I can do harm in the world.

I like to think I do less harm now and actually have begun to accept what it means to be white in America – to do the work to be an anti-racist. I continue to look at the ways large and small that I uphold white supremacy culture. “After all, black and brown people have been resisting, uprising, and protesting in this country for centuries. If that were enough, it would have worked already. The missing link is white people doing deep, honest, and ongoing inventories (and clean-up) of their own relationship to white supremacy.”(Quote from TIME Article)

I need to continue to speak out, to help hold other white people accountable, to think about race. Sometimes when power shifts, when we change our culture, from one of white supremacy, those who benefited from it feel attacked, feel a loss, or feel left out. I hope that in our communities across this country we who are white can move through these feelings – “…it is white people (especially progressive white people) who are responsible for what happens now. Either they work to understand – and change – how white supremacy moves in and through their lives, hearts, minds, and spaces, or they decide they don’t have time, they’re too scared, they can’t deal with it,”(Quote from TIME Article)

The experience of making a mistake and having it pointed out – felt to me at the time as humiliating, painful, and overwhelming – now has become a touchstone point of change and transformation for me. I had to own my power and step aside.

We are shifting who leads and drives our work at Columbia Legal Services; we are thinking about race in our advocacy; we are seeing budgeting as a moral and inclusive process; we are caucusing to take time to think about race in our lives and work; we are thinking about how development works and how it can be part of community building, we are having difficult conversations; we are learning more about restorative justice; we are including equity in our feedback and in our hiring; we are thinking and reading about issues in our Hungry for Equity program; we are trying to be more transparent in decision making; value different types of expertise and lived experience; take risks; acknowledge historic wrongs as an organization; to be accountable; to speak truth to power; to learn how to take responsibility for our impact; tell our stories; listen.

We are committed to this work even when we do it imperfectly, make mistakes, are afraid, revert to old practices, or take three steps forward and then two steps back and have conflict. Race equity work, systemic and organizational change is messy and it’s necessary and there is not a finish line. And there is beauty, joy, and humor in this work.

My hope is that we all can continue to come together in solidarity to move toward being a more anti-racist community to transform ourselves, our organizations, and our world.

Merf Ehman

Executive Director

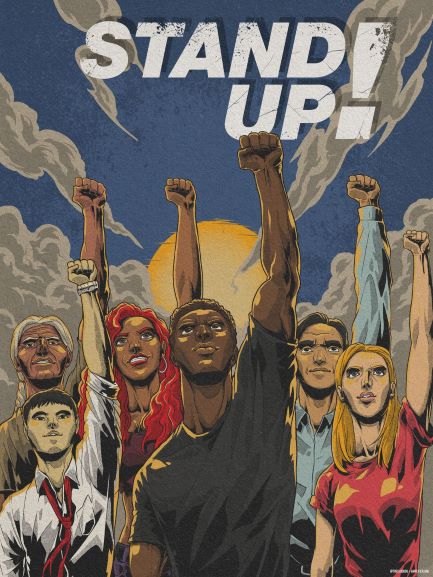

(Art by Tres Kiddos)

Recent Comments